How to Improve Your Drawing Skills with Simple Shapes

How to Improve Your Drawing Skills with Simple Shapes

Embarking on a creative journey in art is a thrilling adventure, full of possibilities. But where do you start when faced with a blank page? For many, the impulse is to dive straight into complex portraits or elaborate scenes, only to feel discouraged. The secret to bypassing that frustration lies not in drawing more, but in drawing simpler.

Simple geometric shapes, often overlooked in their simplicity, are the fundamental building blocks of all artistic expression. Think of them as the alphabet of the visual language; before you can write a novel, you must learn your letters

In this guide, we'll delve into the joy and power of practicing with spheres, cones, cylinders, and cubes. This is your first step toward unlocking your creativity, one shape at a time.

A Personal Review: KraftGeek Plein Air Easel vs. Winsor & Newton Dart Sketching Easel

As someone who paints both in the studio and outdoors, I’m always looking for an easel that’s light, sturdy, and easy to manage. I’ve been using both the KraftGeek Plein Air Easel and the Winsor & Newton Dart Sketching Easel, and while they share similarities in portability and setup, they each have their strengths depending on your painting style and working habits

KraftGeek Plein Air Easel

The KraftGeek Plein Air Easel really stands out for its modern, smart design; it feels sleek and well thought out, with a clean look that makes it just as at home in the studio as out on location. What I noticed right away is how lightweight and easy it is to carry it is, even for me at just 5ft tall. Some easels can feel awkward to lug around, but the KraftGeek’s compact frame and balance make it genuinely comfortable to transport from place to place.

Setup is quick and intuitive, everything locks neatly into place and I had it standing within a couple of minutes. Once it’s up, it feels surprisingly sturdy, especially for a portable easel. It handles mid-sized canvases beautifully (around 16"×20"), and I experienced little to no wobble while painting. I particularly like that it can be used as a tabletop easel or extended for floor use, making it versatile whether I’m working seated or standing.

There are a few quirks, though. The legs can slip if they’re not properly tightened, especially on smooth floors, so it’s worth double-checking the locks before starting. It’s not ideal for very large canvases, as it can start to feel top-heavy, and outdoors it can be a bit too light in strong wind unless you add some weight to the ledge. Still, those are minor issues compared to how well it performs overall.

For me, the KraftGeek hits a sweet spot between portability, stability, and aesthetics. It feels like a thoughtfully designed piece of kit. Perfect for artists who want something functional yet stylish, and especially convenient if you’re on the shorter side and tired of wrestling with awkward, heavy easels.

Winsor & Newton Dart Sketching Easel

The Winsor & Newton Dart is another excellent option for artists who value portability. It’s extremely lightweight (about 1.4 kg) and folds down small enough to slip into a backpack or art trolley, making it great for quick outdoor sketching sessions. The telescopic legs adjust easily, and the mast can tilt into a horizontal position, which is ideal for watercolour work.

It’s also very easy to set up, and that’s something I really appreciate when painting on location. The Dart is wonderfully convenient for small to medium surfaces, and its ability to adjust for different media such as, watercolour, acrylic, or oil; a real plus!

That said, I found it less stable than the KraftGeek, especially when working with anything larger than A3. The rear leg sometimes slips, and the canvas groove is quite shallow, so a canvas can lean forward unless clipped. While many reviewers flag the screw tightener's intrusive placement, I've found an additional flaw: the screw itself often spins in its housing, making it difficult to secure. This is a minor but frustrating issue when setting up quickly or working outdoors. Ultimately, it's a serviceable easel for light use, but I wouldn't trust it for vigorous painting or heavy impasto techniques.

Final Thoughts

Both easels have a lot going for them, but they cater to different needs.

The KraftGeek Plein Air Easel feels sturdier and more refined, with a balanced design that’s easy to carry even for someone petite like me. It’s perfect for studio use or painting outdoors on calm days, and its modern look makes it feel like a proper upgrade from typical metal tripods.

The Winsor & Newton Dart Sketching Easel is a great lightweight travel companion, ideal for quick sketches, watercolour, or small-scale work. It’s incredibly portable, but not quite as solid or secure when you need real stability.

If you want a stylish, reliable easel that’s both portable and practical, the KraftGeek is the one I’d recommend. But if your priority is ultralight convenience for sketching or watercolour on the go, the Dart still holds its place.

Visit this link to purchase a KraftGeek Plein Air Easel and use the discount code BCS15 to save 15% on your order.

Beyond the Horizon: Unlocking the Two Powerful Meanings of Perspective in Art

Have you ever stood before a breathtaking Renaissance painting and felt you could step right into the scene? Or have you looked at a modern abstract piece and been deeply moved, while a friend was left completely cold? The secret behind both experiences lies in a single, powerful word: Perspective.

In art, "perspective" is a chameleon of a term. It refers to both the technical tricks artists use to create the illusion of depth on a flat surface, and the unique lens of experience through which they see—and we interpret—the world. Let's unravel these two meanings and discover how they shape everything we see in art.

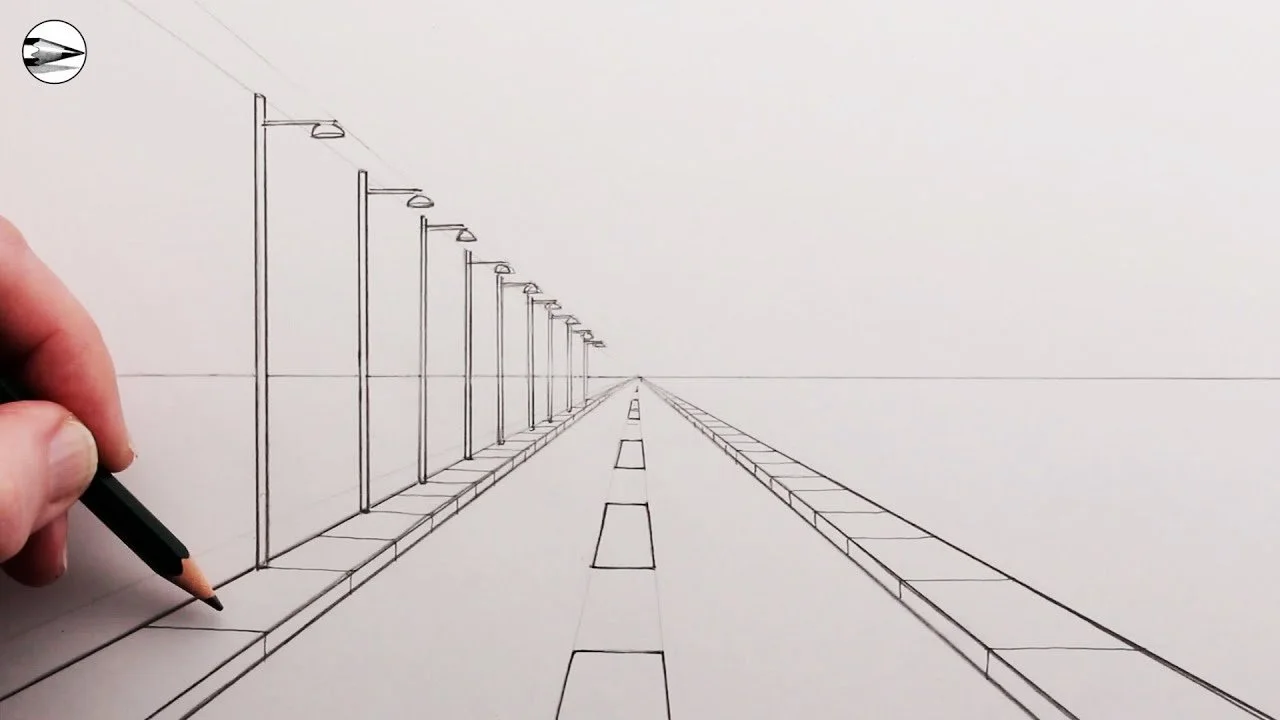

The Technical View: Linear Perspective and the Illusion of Depth

This is the "how-to" of perspective—the mathematical and geometric system that gives a two-dimensional artwork a sense of three-dimensional space.

The Renaissance Revolution: Before the 15th century, artworks often looked flat. Figures were sized by importance, not by their position in space. Then, artists like Filippo Brunelleschi formalized linear perspective. The core principle is simple: parallel lines receding into the distance appear to converge at a single point on the horizon called the vanishing point.

Why It Matters: This technique was revolutionary. It allowed artists to create stunningly realistic scenes, making viewers feel like they were looking through a window into another world. From the architectural precision of Da Vinci's "The Last Supper" to the sprawling cityscapes of Canaletto, linear perspective became the foundation for Western art for centuries.

Quick Tip for Artists: To see this in action, look down a straight road or railway track. Notice how the parallel sides seem to meet at a point far in the distance. That’s your vanishing point!

2. The Personal View: The Artist's and Viewer's Lens

Beyond technique, perspective is also deeply personal. It's about point of view—the internal framework of beliefs, experiences, and emotions that an artist brings to their work, and that we, as viewers, bring when we interpret it.

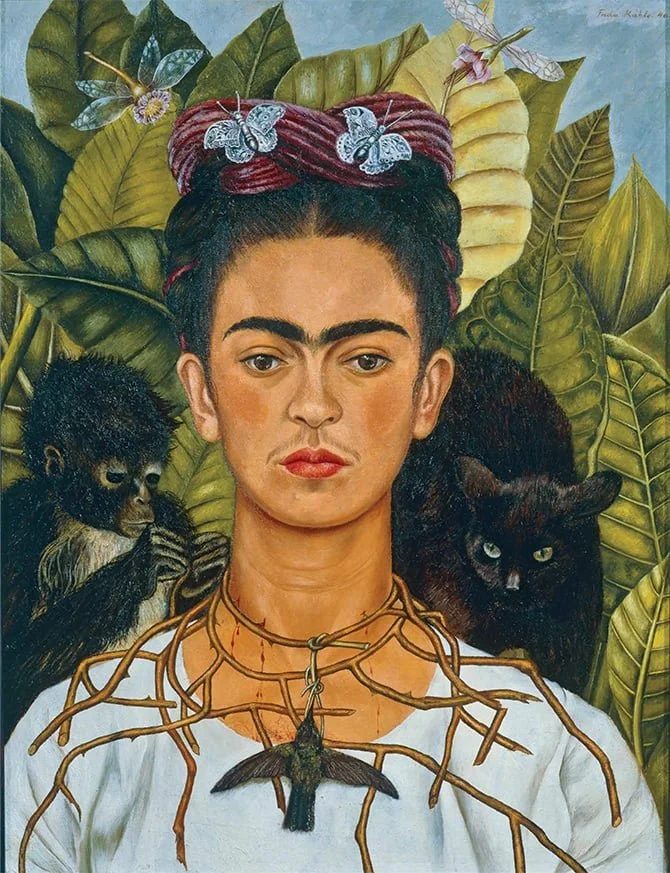

The Artist's Perspective: An artist's work is a filter for their soul. Frida Kahlo's self-portraits are steeped in the perspective of physical pain and cultural identity. Banksy's street art is shaped by a perspective of political rebellion. Their individual experiences directly dictate their subject matter, style, and message.

The Viewer's Perspective: We are not blank slates. Your personal history, mood, and cultural background actively shape how you see art. A painting of a stormy sea might feel terrifying to one person who fears the ocean and exhilarating to another who is an avid sailor. This is why art is so powerfully subjective; there is no single "correct" interpretation.

Where the Two Meanings Meet

The true magic happens when technical and personal perspective intertwine. Imagine two artists painting the same street scene.

Artist A uses a low vanishing point, making the buildings loom tall and powerful, perhaps reflecting their feeling of awe in the city.

Artist B uses a high vanishing point, looking down on the scene, making the people and cars seem small and anonymous, perhaps commenting on urban isolation.